Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma: Difference between revisions

Jack.Dewey (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Jack.Dewey (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

|OMIM = | |OMIM = | ||

|EyeWiki = | |EyeWiki = | ||

|Radiopaedia = https://radiopaedia.org/articles/juvenile-nasopharyngeal-angiofibroma?lang=us | |Radiopaedia = [https://radiopaedia.org/articles/juvenile-nasopharyngeal-angiofibroma?lang=us Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma] | ||

|Pathology = [https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/nasalangiofibroma.html Nasal Angiofibroma] | |||

}} | }} | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a benign vascular neoplasm of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx that classically presents in adolescent boys. | '''Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA)''' is a benign vascular neoplasm of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx that classically presents in adolescent boys. | ||

== Pathophysiology == | == Pathophysiology == | ||

=== Relevant Anatomy === | === Relevant Anatomy === | ||

JNA's typically originate in the region of the sphenopalatine artery (SPA) in the posterior nasal cavity/nasopharynx. From there, they can extend into the paranasal sinuses, pterygopalatine fossa (PPF), infratemporal fossa (ITF), orbit, or cranial vault. | |||

<gallery> | |||

Pterygopalatine fossa.jpg|Cadaveric model of the PPF | |||

Schematic diagram showing the bony anatomy and main neural connections of the PPF.png|Neural contents of the PPF | |||

Gray511.png|Maxillary artery branches, with SPA at the distal end | |||

Gerrish's Text-book of Anatomy (1902) - Fig. 243.png|Location of the sphenopalatine foramen | |||

Basilar process and palatine process.jpg|Location of the ITF | |||

</gallery> | |||

=== Disease Etiology === | === Disease Etiology === | ||

JNA's are fibrovascular tumors that arise from the posterior lateral nasal cavity near the choana. There is substantial debate about the exact circumstances and location that lead to the formation of a JNA, but they are generally accepted to form near the region of the sphenopalatine foramen. Proposed theories regarding their etiology include androgen receptor-related growth,<ref name="Liu 2015">Liu Z, Wang J, Wang H, Wang D, Hu L, Liu Q, Sun X. Hormonal receptors and vascular endothelial growth factor in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: immunohistochemical and tissue microarray analysis. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2015 Jan 2;135(1):51-7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2014.952774</ref> incomplete regression of a branchial artery during embryogenesis,<ref name="Schick 2002">Schick B, Plinkert PK, Prescher A. Aetiology of angiofibromas: reflection on their specific vascular component. Laryngo-rhino-otologie. 2002 Apr 1;81(4):280-4. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-25322</ref> oncogenic mutations in C-MYC and C-KIT,<ref name="Pandey 2017">Pandey P, Mishra A, Tripathi AM, Verma V, Trivedi R, Singh HP, Kumar S, Patel B, Singh V, Pandey S, Pandey A. Current molecular profile of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: first comprehensive study from India. The Laryngoscope. 2017 Mar;127(3):E100-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26250</ref> and a wide variety of other genetic aberrations. | |||

===Epidemiology=== | |||

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma has been reported to be the most common benign neoplasm of the nasopharynx in young males. It accounts for 0.05% to 0.5% of all head and neck tumors, with a reported incidence of 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 60,000 in the US annually.<ref name="Boghani 2013">Boghani Z, Husain Q, Kanumuri VV, Khan MN, Sangvhi S, Liu JK, Eloy JA. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review and comparison of endoscopic, endoscopic‐assisted, and open resection in 1047 cases. The Laryngoscope. 2013 Apr;123(4):859-69. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23843</ref><ref name="Ferouz 1995">Ferouz AS, Mohr RM, Paul P. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma and familial adenomatous polyposis: an association?. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 1995 Oct;113(4):435-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-59989570081-1</ref><ref name="Huang 2014">Huang Y, Liu Z, Wang J, Sun X, Yang L, Wang D. Surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: analysis of 162 cases from 1995 to 2012. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Aug;124(8):1942-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24522</ref> It classically presents in adolescent males, with a typical age of presentation between 13 and 22 years old.<ref name ="Newman 2023">Newman M, Nguyen TB, McHugh T, Reddy K, Sommer DD. Early-onset juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA): a systematic review. Journal of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 2023 Dec;52(1):s40463-023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-023-00687-w</ref> | |||

=== Genetics === | === Genetics === | ||

There is no identified definitive genetic locus that predisposes patients to JNA's. However, there have been a number of studies looking at the various genetic components that could influence their formation.<ref name="Doody 2019">Doody J, Adil EA, Trenor III CC, Cunningham MJ. The genetic and molecular determinants of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2019 Nov;128(11):1061-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419850194</ref> Due to fact that JNA's classically form in adolescent males, there have been several studies focused on the possible hormonal influence on their formation and growth. JNA's tend to have an abundance of progesterone and estradiol, but a relatively lower concentration of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone.<ref name="Kumagami 05 1993">Kumagami H. Estradiol, dihydrotestosterone, and testosterone in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma tissue. American Journal of Rhinology. 1993 May;7(3):101-4. https://doi.org/10.2500/105065893781976393</ref><ref name="Kumagami 01 1993">Kumagami H. Sex hormones in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma tissue. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1993 Jan 1;20(2):131-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0385-8146(12)80240-9</ref> Supplemental testosterone was trialed in JNA patients, but both tumor growth<ref name="Johnsen 1966">Johnsen S, Kloster JH, Schiff M. The action of hormones on juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1966 Jan 1;61(1-6):153-60. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016486609127052</ref> and tumor recurrence<ref name="Riggs 2010">Riggs S, Orlandi RR. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma recurrence associated with exogenous testosterone therapy. Head & Neck: Journal for the Sciences and Specialties of the Head and Neck. 2010 Jun;32(6):812-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21152</ref> have been documented. Papers investigating potential targeted therapy markers have looked at steroid hormones, chromosomal abnormalities, growth factors, and other intracellular molecular targets.<ref name="Doody 2019"></ref> There have been studies investigating a possible link between Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and JNA's via the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)/β-catenin pathway, but no specific genetic link has been identified as of yet.<ref name="Guertl 2000">Guertl B, Beham A, Zechner R, Stammberger H, Hoefler G. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an AM-Gene-Associated tumor?. Human pathology. 2000 Nov 1;31(11):1411-3.</ref> | |||

=== Histology === | === Histology === | ||

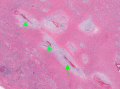

Grossly on histologic section there are large fibrous/collagenous sections with fibroblasts, as well as vascular spaces of various sizes throughout the tumor.<ref name="Xu 2020">Xu B. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/nasalangiofibroma.html. Accessed November 17th, 2024.</ref> The stromal cells have an abundance of beta-catenin relative to the vascular endothelial cells. | |||

<gallery> | |||

JNA 30x.png|H&E stained section of green inked vascular channel (30x) | |||

Beta Catenin JNA.png|Abnormal nuclear expression in stromal cells (blue arrow), compared with membranous / cytoplasmic staining in the endothelial cells (red arrow) | |||

</gallery> | |||

== Diagnosis == | == Diagnosis == | ||

=== Patient History === | === Patient History === | ||

Patients may have a history of any of the following symptoms: | |||

* Unilateral nasal obstruction | |||

* Recurrent epistaxis | |||

* High-volume epistaxis | |||

* Eustachian tube dysfunction | |||

* Headache | |||

* Facial swelling | |||

* Anosmia / Hyposmia | |||

* Cranial neuropathy | |||

* Vision changes | |||

=== Physical Examination === | === Physical Examination === | ||

Many patients will not have obvious findings on anterior rhinoscopy. A large vascular-appearing mass is commonly fond on nasal endoscopy on the posterior lateral nasal sidewall near the region of the sphenopalatine artery. Note that '''''these hypervascular masses should not be biopsied''''', as this may result in significant bleeding that is hard to control in the clinic setting. | |||

=== Laboratory Tests === | === Laboratory Tests === | ||

Laboratory tests are not commonly useful in the diagnosis of JNA's, but should be performed preoperatively in the case of a planned surgical resection. | |||

* Hemoglobin / Hematocrit | |||

* Platelet level | |||

* Platelet function (if family history of platelet dysfunction) | |||

* PT / INR | |||

* Blood Type and Screen (all patients) | |||

* Blood Type and Cross (patients with advanced stage tumors where a significant blood loss is expected) | |||

=== Imaging === | === Imaging === | ||

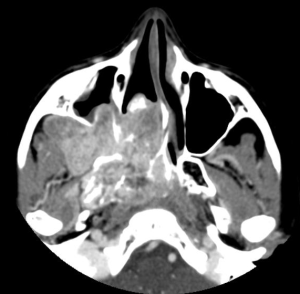

[ | [[File:Holman-Miller Sign.png|right|thumb|300 px|Axial CT scan of a JNA showing a right-sided Holman Miller sign]] | ||

CT scan, angiography, and MRI are all useful in the workup of JNA's and have differing benefits.<ref name="Gaillard 2008">Gaillard F, Walizai T, Bell D, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 Nov 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-1541</ref> CT is typically the first imaging modality ordered in these patients, and is helpful for delineating the extent of bony erosion. Angiography demonstrates the extent of the mass well, and is frequently used in pre-operative embolization 24-48 hours before surgical resection. A majority of JNA's are supplied by the external carotid system, either by the maxillary artery (SPA) or the ascending pharyngeal artery.<ref name="Gaillard 2008"></ref> A lesser fraction of tumors are supplied by the internal carotid system (ophthalmic or sphenoidal branches), and this is typically in larger masses with intracranial invasion. MRI can be used to assess for intraorbital or intracranial extension. JNA's are T1 intermediate, T2 heterogenous with flow voids, and enhance with Gadolinium. The following are general characteristics often found in imaging of JNA's: | |||

* Highly vascular nasopharyngeal mass | |||

* Holman-Miller Sign<ref name="Niknejad 2013">Niknejad M, Tatco V, Bell D, et al. Holman-Miller sign (maxillary sinus). Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 Nov 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-21804</ref>: Anterior displacement of the posterior maxillary wall due to mass effect from the tumor | |||

* Widening of the PMF or PPF | |||

* Erosion of the pterygoid plate, especially the medial plate | |||

There are several | There are several classification systems that have been proposed for JNAs based on imaging findings. | ||

{| class="wikitable", style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none; text-align: center" | {| class="wikitable", style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none; text-align: center" | ||

|+ | |+ Classification Systems for Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibromas | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Classification System !! style=width:15em | Stage I !! style=width:15em | Stage II !! style=width:15em | Stage III !! style=width:15em | Stage IV !! style=width:15em | Stage V | ! Classification System !! style=width:15em | Stage I !! style=width:15em | Stage II !! style=width:15em | Stage III !! style=width:15em | Stage IV !! style=width:15em | Stage V | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Andrews<ref>Andrews JC, Fisch U, Aeppli U, Valavanis A, Makek MS. The surgical management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with the infratemporal fossa approach. The Laryngoscope. 1989 Apr;99(4):429-37.</ref> || Confined to NP || Invading one of the following with evidence of bony erosion: PPF, MS, ES, or SS || Invading ITF or orbit<br>'''IIIa''': No intracranial extension<br>'''IIIb''': Extradural (parasellar) extension || Intradural extension<br>'''IVa''': No infiltration of CS, PF, or OC<br>'''IVb''': Infiltration of CS, PF, or OC || -- | | Andrews (1989)<ref name="Andrews 1989">Andrews JC, Fisch U, Aeppli U, Valavanis A, Makek MS. The surgical management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with the infratemporal fossa approach. The Laryngoscope. 1989 Apr;99(4):429-37. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198904000-00013</ref> || Confined to NP || Invading one of the following with evidence of bony erosion: PPF, MS, ES, or SS || Invading ITF or orbit<br><br>'''IIIa''': No intracranial extension<br>'''IIIb''': Extradural (parasellar) extension || Intradural extension<br><br>'''IVa''': No infiltration of CS, PF, or OC<br>'''IVb''': Infiltration of CS, PF, or OC || -- | ||

|- | |||

| Chandler (1984)<ref name="Chandler 1984">Chandler JR, Moskowitz L, Goulding R, Quencer RM. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: staging and management. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 1984 Jul;93(4):322-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348948409300408</ref> || Confined to NP || Extension into the nasal cavity, SS, or both || Extension into any of the following: antrum, ES, PMF, ITF, orbit, or cheek || Intracranial extension || -- | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Onerci (2006)<ref name="Onerci 2006">Onerci M, Oğretmenoğlu O, Yücel T. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a revised staging system. Rhinology. 2006 Mar 1;44(1):39-45. PMID: 16550949</ref>|| Nose, NP, ES, and SS or minimal extension into PMF || MS involvement, full occupation of PMF, extension to anterior cranial fossa, limited extension into ITF || Deep extension into cancellous bone at pterygoid base or body and GW of sphenoid, significant lateral extension into ITF or pterygoid plates, orbital involvement, CS obliteration || Intracranial extension between pituitary gland and ICA, tumor localization lateral to ICA, middle fossa extension and extensive intracranial extension || -- | ||

|- | |||

| Radkowski (1996)<ref name="Radkowski 1996">Radkowski D, McGill T, Healy GB, Ohlms L, Jones DT. Angiofibroma: changes in staging and treatment. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 1996 Feb 1;122(2):122-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140012004</ref>|| '''IA''': Confined to nose or NP<br>'''IB''': Extends into one or more sinuses || '''IIa''': Minimal extension into medial PMF<br>'''IIb''': Full occupation of PMF with local mass effect<br>'''IIc''': Extension into ITF, cheek, or posterior to pterygoid plates || Erosion of skull base<br><br>'''IIIa''': Minimal skull base involvement<br>'''IIIb''': Extensive intracranial extension, with or without invasion into CS || -- || -- | |||

|- | |||

| Sessions (1981)<ref name="Sessions 1981">Sessions RB, Bryan RN, Naclerio RM, Alford BR. Radiographic staging of juvenile angiofibroma. Head & neck surgery. 1981 Mar;3(4):279-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.2890030404</ref> || '''IA''': Confined to nose or NP<br>'''IB''': Extends into one or more sinuses || '''IIa''': Minimal extension into PMF<br>'''IIb''': Full occupation of PMF with or without orbital erosion<br>'''IIc''': ITF with or without cheek extension || Intracranial extension || -- || -- | |||

|- | |||

| UPMC (2010)<ref name="Snyderman 2010">Snyderman CH, Pant H, Carrau RL, Gardner P. A new endoscopic staging system for angiofibromas. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2010 Jun 21;136(6):588-94. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2010.83</ref> || Nasal cavity, medial PPF || Paranasal sinuses, lateral PPF; no residual vascularity || Skull base erosion, orbit, ITF involvement; no residual vascularity || Skull base erosion, orbit, ITF involvement; residual vascularity || Intracranial extension with residual vascularity<br><br>'''M''': Medial extension<br>'''L''': Lateral extension | |||

|- | |||

|+ style="caption-side:bottom; font-weight: normal;"|''Abbreviations: Cavernous sinus (CS), Ethmoid sinus (ES), Infratemporal fossa (ITF), Internal carotid artery (ICA), Maxillary sinus (MS), Nasopharynx (NP), Optic chiasm (OC), Pituitary fossa (PF), Pterygomaxillary fissure (PMF), Pterygopalatine fossa (PPF), Sphenoid sinus (SS)'' | |||

|} | |} | ||

=== Differential Diagnosis === | === Differential Diagnosis === | ||

In the case of a nasopharyngeal mass, the following should also be considered: | |||

* Clival chondroma | |||

* Encephalocele | |||

* Esthesioneuroblastoma | |||

* Inverted papilloma | |||

* Nasal polyp | |||

* Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | |||

* Nasopharyngeal teratoma | |||

* Rhabdomyosarcoma | |||

* Vascular malformation | |||

== Management == | == Management == | ||

=== Medical Management === | === Medical Management === | ||

There is no approved medical treatment for management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. The treatment is primarily surgical. Medical management focuses on optimizing patients before surgery, such as addressing any coagulopathies or addressing underlying anemia. | |||

=== Surgical Management === | === Surgical Management === | ||

Historically, surgical management of JNAs involved aggressive open approaches, including transpalatal, lateral rhinotomy, midface degloving, or infratemporal fossa craniotomy approaches.<ref name="Renkonen 2011">Renkonen S, Hagström J, Vuola J, Niemelä M, Porras M, Kivivuori SM, Leivo I, Mäkitie AA. The changing surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology. 2011 Apr;268:599-607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1383-z</ref> In recent years, there has been a transition towards transnasal endoscopic approaches. This has resulted in better visualization during surgery and a subsequent improvement in intraoperative blood loss, need for blood transfusions,<ref name="Oliveira 2012">Oliveira JA, Tavares MG, Aguiar CV, Azevedo JF, Sousa JR, Almeida PC, Gomes EF. Comparison between endoscopic and open surgery in 37 patients with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Brazilian Journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2012;78:75-80. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1808-86942012000100012</ref> and recurrence rates.<ref name="Bosraty 2011">Bosraty H, Atef A, Aziz M. Endoscopic vs. open surgery for treating large, locally advanced juvenile angiofibromas: A comparison of local control and morbidity outcomes. ENT: Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2011 Nov 1;90(11). PMID: 22109921</ref> Prior to surgery, preoperative embolization should be considered to limit blood loss intraoperatively. | |||

== Outcomes == | == Outcomes == | ||

=== Complications === | === Complications === | ||

The primary concerns in the surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma are bleeding and recurrence rates. Iatrogenic injuries to structures of the orbit (such as ophthalmoplegia) and skull base (such as facial paresthesias) are also a concern depending on the degree of tumor extension. | |||

==== Bleeding ==== | |||

Intraoperative bleeding rates vary based on technique, whether preoperative embolization was used, and tumor staging. Endoscopic surgery is generally accepted to have lower intraoperative blood loss relative to more traditional open approaches.<ref name="Oliveira 2012"></ref> Preoperative embolization has also been found to significantly lower intraoperative blood loss. One study of 47 patients (primarily Radkowski stages I-II) found that patients who underwent preoperative embolization had a mean estimated blood loss (EBL) of 770 mL, and patients who did not undergo embolization had a mean EBL of more than 1,400 mL.<ref name="Ardehali 2010">Ardehali MM, Ardestani SH, Yazdani N, Goodarzi H, Bastaninejad S. Endoscopic approach for excision of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: complications and outcomes. American journal of otolaryngology. 2010 Sep 1;31(5):343-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.007</ref> The same study noted that embolized patients had a mean hospital stay of 1.8 days, vs 3.1 days for all patients in the study. A systematic review of advance-stage JNAs with intracranial extension found a mean EBL of 1,700 mL and a similar reduction in EBL following preoperative embolization.<ref name="Leong 2013">Leong SC. A systematic review of surgical outcomes for advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with intracranial involvement. The Laryngoscope. 2013 May;123(5):1125-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23760</ref> | |||

==== Recurrence ==== | |||

Recurrence rates are similarly related to surgical technique and tumor stage. Endoscopic approaches have been documented to have an improved recurrence rate relative to open approaches.<ref name="Bosraty 2011"></ref> A systematic review of 92 studies totaling 821 patients found a recurrence rate of about 10%, as well as 7.7% with residual tumor.<ref name="Khoueir 2013">Khoueir N, Nicolas N, Rohayem Z, Haddad A, Abou Hamad W. Exclusive endoscopic resection of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Mar;150(3):350-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813516605</ref> Studies looking at more invasive tumors have a higher rate of recurrence of approximately 18%.<ref name="Leong 2013"></ref> | |||

=== Prognosis === | === Prognosis === | ||

Recurrence rates can be very high and increase with increased stage at the time of surgery. Recurrence has been reported from 22%<ref name="Bleier 2009">Bleier BS, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN, Chiu AG, Bloom JD, O'Malley Jr BW. Current management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a tertiary center experience 1999–2007. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2009 May;23(3):328-30. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3322</ref> to as high as 61% in advanced disease.<ref name="Huang 2014">Huang Y, Liu Z, Wang J, Sun X, Yang L, Wang D. Surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: analysis of 162 cases from 1995 to 2012. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Aug;124(8):1942-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24522</ref> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:04, 18 November 2024

Overview

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a benign vascular neoplasm of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx that classically presents in adolescent boys.

Pathophysiology

Relevant Anatomy

JNA's typically originate in the region of the sphenopalatine artery (SPA) in the posterior nasal cavity/nasopharynx. From there, they can extend into the paranasal sinuses, pterygopalatine fossa (PPF), infratemporal fossa (ITF), orbit, or cranial vault.

-

Cadaveric model of the PPF

-

Neural contents of the PPF

-

Maxillary artery branches, with SPA at the distal end

-

Location of the sphenopalatine foramen

-

Location of the ITF

Disease Etiology

JNA's are fibrovascular tumors that arise from the posterior lateral nasal cavity near the choana. There is substantial debate about the exact circumstances and location that lead to the formation of a JNA, but they are generally accepted to form near the region of the sphenopalatine foramen. Proposed theories regarding their etiology include androgen receptor-related growth,[1] incomplete regression of a branchial artery during embryogenesis,[2] oncogenic mutations in C-MYC and C-KIT,[3] and a wide variety of other genetic aberrations.

Epidemiology

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma has been reported to be the most common benign neoplasm of the nasopharynx in young males. It accounts for 0.05% to 0.5% of all head and neck tumors, with a reported incidence of 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 60,000 in the US annually.[4][5][6] It classically presents in adolescent males, with a typical age of presentation between 13 and 22 years old.[7]

Genetics

There is no identified definitive genetic locus that predisposes patients to JNA's. However, there have been a number of studies looking at the various genetic components that could influence their formation.[8] Due to fact that JNA's classically form in adolescent males, there have been several studies focused on the possible hormonal influence on their formation and growth. JNA's tend to have an abundance of progesterone and estradiol, but a relatively lower concentration of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone.[9][10] Supplemental testosterone was trialed in JNA patients, but both tumor growth[11] and tumor recurrence[12] have been documented. Papers investigating potential targeted therapy markers have looked at steroid hormones, chromosomal abnormalities, growth factors, and other intracellular molecular targets.[8] There have been studies investigating a possible link between Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and JNA's via the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)/β-catenin pathway, but no specific genetic link has been identified as of yet.[13]

Histology

Grossly on histologic section there are large fibrous/collagenous sections with fibroblasts, as well as vascular spaces of various sizes throughout the tumor.[14] The stromal cells have an abundance of beta-catenin relative to the vascular endothelial cells.

-

H&E stained section of green inked vascular channel (30x)

-

Abnormal nuclear expression in stromal cells (blue arrow), compared with membranous / cytoplasmic staining in the endothelial cells (red arrow)

Diagnosis

Patient History

Patients may have a history of any of the following symptoms:

- Unilateral nasal obstruction

- Recurrent epistaxis

- High-volume epistaxis

- Eustachian tube dysfunction

- Headache

- Facial swelling

- Anosmia / Hyposmia

- Cranial neuropathy

- Vision changes

Physical Examination

Many patients will not have obvious findings on anterior rhinoscopy. A large vascular-appearing mass is commonly fond on nasal endoscopy on the posterior lateral nasal sidewall near the region of the sphenopalatine artery. Note that these hypervascular masses should not be biopsied, as this may result in significant bleeding that is hard to control in the clinic setting.

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests are not commonly useful in the diagnosis of JNA's, but should be performed preoperatively in the case of a planned surgical resection.

- Hemoglobin / Hematocrit

- Platelet level

- Platelet function (if family history of platelet dysfunction)

- PT / INR

- Blood Type and Screen (all patients)

- Blood Type and Cross (patients with advanced stage tumors where a significant blood loss is expected)

Imaging

CT scan, angiography, and MRI are all useful in the workup of JNA's and have differing benefits.[15] CT is typically the first imaging modality ordered in these patients, and is helpful for delineating the extent of bony erosion. Angiography demonstrates the extent of the mass well, and is frequently used in pre-operative embolization 24-48 hours before surgical resection. A majority of JNA's are supplied by the external carotid system, either by the maxillary artery (SPA) or the ascending pharyngeal artery.[15] A lesser fraction of tumors are supplied by the internal carotid system (ophthalmic or sphenoidal branches), and this is typically in larger masses with intracranial invasion. MRI can be used to assess for intraorbital or intracranial extension. JNA's are T1 intermediate, T2 heterogenous with flow voids, and enhance with Gadolinium. The following are general characteristics often found in imaging of JNA's:

- Highly vascular nasopharyngeal mass

- Holman-Miller Sign[16]: Anterior displacement of the posterior maxillary wall due to mass effect from the tumor

- Widening of the PMF or PPF

- Erosion of the pterygoid plate, especially the medial plate

There are several classification systems that have been proposed for JNAs based on imaging findings.

| Classification System | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | Stage V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews (1989)[17] | Confined to NP | Invading one of the following with evidence of bony erosion: PPF, MS, ES, or SS | Invading ITF or orbit IIIa: No intracranial extension IIIb: Extradural (parasellar) extension |

Intradural extension IVa: No infiltration of CS, PF, or OC IVb: Infiltration of CS, PF, or OC |

-- |

| Chandler (1984)[18] | Confined to NP | Extension into the nasal cavity, SS, or both | Extension into any of the following: antrum, ES, PMF, ITF, orbit, or cheek | Intracranial extension | -- |

| Onerci (2006)[19] | Nose, NP, ES, and SS or minimal extension into PMF | MS involvement, full occupation of PMF, extension to anterior cranial fossa, limited extension into ITF | Deep extension into cancellous bone at pterygoid base or body and GW of sphenoid, significant lateral extension into ITF or pterygoid plates, orbital involvement, CS obliteration | Intracranial extension between pituitary gland and ICA, tumor localization lateral to ICA, middle fossa extension and extensive intracranial extension | -- |

| Radkowski (1996)[20] | IA: Confined to nose or NP IB: Extends into one or more sinuses |

IIa: Minimal extension into medial PMF IIb: Full occupation of PMF with local mass effect IIc: Extension into ITF, cheek, or posterior to pterygoid plates |

Erosion of skull base IIIa: Minimal skull base involvement IIIb: Extensive intracranial extension, with or without invasion into CS |

-- | -- |

| Sessions (1981)[21] | IA: Confined to nose or NP IB: Extends into one or more sinuses |

IIa: Minimal extension into PMF IIb: Full occupation of PMF with or without orbital erosion IIc: ITF with or without cheek extension |

Intracranial extension | -- | -- |

| UPMC (2010)[22] | Nasal cavity, medial PPF | Paranasal sinuses, lateral PPF; no residual vascularity | Skull base erosion, orbit, ITF involvement; no residual vascularity | Skull base erosion, orbit, ITF involvement; residual vascularity | Intracranial extension with residual vascularity M: Medial extension L: Lateral extension |

Differential Diagnosis

In the case of a nasopharyngeal mass, the following should also be considered:

- Clival chondroma

- Encephalocele

- Esthesioneuroblastoma

- Inverted papilloma

- Nasal polyp

- Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Nasopharyngeal teratoma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Vascular malformation

Management

Medical Management

There is no approved medical treatment for management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. The treatment is primarily surgical. Medical management focuses on optimizing patients before surgery, such as addressing any coagulopathies or addressing underlying anemia.

Surgical Management

Historically, surgical management of JNAs involved aggressive open approaches, including transpalatal, lateral rhinotomy, midface degloving, or infratemporal fossa craniotomy approaches.[23] In recent years, there has been a transition towards transnasal endoscopic approaches. This has resulted in better visualization during surgery and a subsequent improvement in intraoperative blood loss, need for blood transfusions,[24] and recurrence rates.[25] Prior to surgery, preoperative embolization should be considered to limit blood loss intraoperatively.

Outcomes

Complications

The primary concerns in the surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma are bleeding and recurrence rates. Iatrogenic injuries to structures of the orbit (such as ophthalmoplegia) and skull base (such as facial paresthesias) are also a concern depending on the degree of tumor extension.

Bleeding

Intraoperative bleeding rates vary based on technique, whether preoperative embolization was used, and tumor staging. Endoscopic surgery is generally accepted to have lower intraoperative blood loss relative to more traditional open approaches.[24] Preoperative embolization has also been found to significantly lower intraoperative blood loss. One study of 47 patients (primarily Radkowski stages I-II) found that patients who underwent preoperative embolization had a mean estimated blood loss (EBL) of 770 mL, and patients who did not undergo embolization had a mean EBL of more than 1,400 mL.[26] The same study noted that embolized patients had a mean hospital stay of 1.8 days, vs 3.1 days for all patients in the study. A systematic review of advance-stage JNAs with intracranial extension found a mean EBL of 1,700 mL and a similar reduction in EBL following preoperative embolization.[27]

Recurrence

Recurrence rates are similarly related to surgical technique and tumor stage. Endoscopic approaches have been documented to have an improved recurrence rate relative to open approaches.[25] A systematic review of 92 studies totaling 821 patients found a recurrence rate of about 10%, as well as 7.7% with residual tumor.[28] Studies looking at more invasive tumors have a higher rate of recurrence of approximately 18%.[27]

Prognosis

Recurrence rates can be very high and increase with increased stage at the time of surgery. Recurrence has been reported from 22%[29] to as high as 61% in advanced disease.[6]

References

- ↑ Liu Z, Wang J, Wang H, Wang D, Hu L, Liu Q, Sun X. Hormonal receptors and vascular endothelial growth factor in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: immunohistochemical and tissue microarray analysis. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2015 Jan 2;135(1):51-7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2014.952774

- ↑ Schick B, Plinkert PK, Prescher A. Aetiology of angiofibromas: reflection on their specific vascular component. Laryngo-rhino-otologie. 2002 Apr 1;81(4):280-4. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-25322

- ↑ Pandey P, Mishra A, Tripathi AM, Verma V, Trivedi R, Singh HP, Kumar S, Patel B, Singh V, Pandey S, Pandey A. Current molecular profile of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: first comprehensive study from India. The Laryngoscope. 2017 Mar;127(3):E100-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26250

- ↑ Boghani Z, Husain Q, Kanumuri VV, Khan MN, Sangvhi S, Liu JK, Eloy JA. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review and comparison of endoscopic, endoscopic‐assisted, and open resection in 1047 cases. The Laryngoscope. 2013 Apr;123(4):859-69. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23843

- ↑ Ferouz AS, Mohr RM, Paul P. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma and familial adenomatous polyposis: an association?. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 1995 Oct;113(4):435-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-59989570081-1

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Huang Y, Liu Z, Wang J, Sun X, Yang L, Wang D. Surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: analysis of 162 cases from 1995 to 2012. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Aug;124(8):1942-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24522

- ↑ Newman M, Nguyen TB, McHugh T, Reddy K, Sommer DD. Early-onset juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA): a systematic review. Journal of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 2023 Dec;52(1):s40463-023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-023-00687-w

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Doody J, Adil EA, Trenor III CC, Cunningham MJ. The genetic and molecular determinants of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2019 Nov;128(11):1061-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419850194

- ↑ Kumagami H. Estradiol, dihydrotestosterone, and testosterone in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma tissue. American Journal of Rhinology. 1993 May;7(3):101-4. https://doi.org/10.2500/105065893781976393

- ↑ Kumagami H. Sex hormones in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma tissue. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1993 Jan 1;20(2):131-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0385-8146(12)80240-9

- ↑ Johnsen S, Kloster JH, Schiff M. The action of hormones on juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1966 Jan 1;61(1-6):153-60. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016486609127052

- ↑ Riggs S, Orlandi RR. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma recurrence associated with exogenous testosterone therapy. Head & Neck: Journal for the Sciences and Specialties of the Head and Neck. 2010 Jun;32(6):812-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21152

- ↑ Guertl B, Beham A, Zechner R, Stammberger H, Hoefler G. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an AM-Gene-Associated tumor?. Human pathology. 2000 Nov 1;31(11):1411-3.

- ↑ Xu B. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/nasalangiofibroma.html. Accessed November 17th, 2024.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gaillard F, Walizai T, Bell D, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 Nov 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-1541

- ↑ Niknejad M, Tatco V, Bell D, et al. Holman-Miller sign (maxillary sinus). Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 Nov 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-21804

- ↑ Andrews JC, Fisch U, Aeppli U, Valavanis A, Makek MS. The surgical management of extensive nasopharyngeal angiofibromas with the infratemporal fossa approach. The Laryngoscope. 1989 Apr;99(4):429-37. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198904000-00013

- ↑ Chandler JR, Moskowitz L, Goulding R, Quencer RM. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: staging and management. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 1984 Jul;93(4):322-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348948409300408

- ↑ Onerci M, Oğretmenoğlu O, Yücel T. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a revised staging system. Rhinology. 2006 Mar 1;44(1):39-45. PMID: 16550949

- ↑ Radkowski D, McGill T, Healy GB, Ohlms L, Jones DT. Angiofibroma: changes in staging and treatment. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 1996 Feb 1;122(2):122-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140012004

- ↑ Sessions RB, Bryan RN, Naclerio RM, Alford BR. Radiographic staging of juvenile angiofibroma. Head & neck surgery. 1981 Mar;3(4):279-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.2890030404

- ↑ Snyderman CH, Pant H, Carrau RL, Gardner P. A new endoscopic staging system for angiofibromas. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2010 Jun 21;136(6):588-94. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2010.83

- ↑ Renkonen S, Hagström J, Vuola J, Niemelä M, Porras M, Kivivuori SM, Leivo I, Mäkitie AA. The changing surgical management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology. 2011 Apr;268:599-607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1383-z

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Oliveira JA, Tavares MG, Aguiar CV, Azevedo JF, Sousa JR, Almeida PC, Gomes EF. Comparison between endoscopic and open surgery in 37 patients with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Brazilian Journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2012;78:75-80. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1808-86942012000100012

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bosraty H, Atef A, Aziz M. Endoscopic vs. open surgery for treating large, locally advanced juvenile angiofibromas: A comparison of local control and morbidity outcomes. ENT: Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2011 Nov 1;90(11). PMID: 22109921

- ↑ Ardehali MM, Ardestani SH, Yazdani N, Goodarzi H, Bastaninejad S. Endoscopic approach for excision of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: complications and outcomes. American journal of otolaryngology. 2010 Sep 1;31(5):343-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.007

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Leong SC. A systematic review of surgical outcomes for advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with intracranial involvement. The Laryngoscope. 2013 May;123(5):1125-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23760

- ↑ Khoueir N, Nicolas N, Rohayem Z, Haddad A, Abou Hamad W. Exclusive endoscopic resection of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Mar;150(3):350-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813516605

- ↑ Bleier BS, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN, Chiu AG, Bloom JD, O'Malley Jr BW. Current management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a tertiary center experience 1999–2007. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2009 May;23(3):328-30. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3322