Paraganglioma

Overview

Paragangliomas are masses derived from the paraganglia, a group of non-neuronal cells that are associated with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.

History

These tumors historically were called "glomus tumors" when present in the head and neck. This term has fallen out of use due to potential confusion with other structures with similar names, such as glomus bodies.

Pathophysiology

Relevant Anatomy

The term "paraganglia" refers to a group of non-neuronal neuroendocrine cells derived embryologically from neural crest cells. There are paraganglia associated with the sympathetic nervous system comprised of chromaffin cells, and those associated with the parasympathetic nervous system comprised of glomus cells. The adrenal medulla is the largest collection of Chromaffin cells in the body. The paraganglia of the head and neck region are associated with the glomus cells of the parasympathetic nervous system.

The paraganglia are highly vascularized for the purposes of chemoreceptor sensitivity. Sympathetic paraganglia act as endocrine organs with systemic catecholamine release (such as the adrenal medulla, organ of Zuckerkandl, etc.). These paraganglia are a major source of catecholamines in early embryogenesis (assuming much function of the adrenal medulla). Parasympathetic paraganglia predominantly have more local effects on nerve endings, such as in the carotid body.

-

Target end-organs of the sympathetic nervous system.

-

Target end-organs of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Disease Etiology

Epidemiology

The incidence of head and neck paragangliomas has been reported as 1 in 30,000 to 1 in 100,000. Approximately 10% of patients with head and neck paragangliomas will have multiple masses. As many as 25-35% of cases have been linked to hereditary conditions, typically Familial Paraganglioma Syndrome (see Genetics section below). There is an equal distribution of carotid paragangliomas in men and women, but jugulotympanic paragangliomas are six times more likely to be in women.

Genetics

Histology

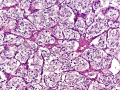

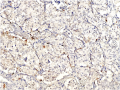

There are two predominant cell types seen on histologic sections of paragangliomas. Type I cells, also known as Glomus Cells, are comprised of secretory cells and make up a majority of the bulk of paragangliomas. Type I cells will stain positive for neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and CD56. Type II cells, also known as Sustentacular Cells, is comprised of Schwann-like satellite cells. Type II cells stain positive for S100 and occasionally glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Paragangliomas will arrange themselves in the same histologic morphology as normal paraganglia tissue, in what is described as the Zellballen configuration - an arrangement of clusters of Type I cells in a surrounding stroma of Type II cells.

-

Paraganglioma section at 20x demonstrating the Zellballen configuration.

-

Synaptophysin staining highlighting the Type I cells.

-

S100 staining highlighting the Type II cells.

Diagnosis

Patient History

Most patients present for evaluation in their 40s or 50s.

Physical Examination

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory workup of paragangliomas should focus identifying whether the mass is a secretory paraganglioma by assessing for the presence of metanephrines and/or their metabolites:

- Urine metanephrines

- Urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA)

- Urine homovanillic acid (HVA)

- Plasma metanephrines

- Plasma vanillylmandelic acid (VMA)

- Plasma homovanillic acid (HVA)

These are typically expensive tests that will need to be sent out. They may be bundled or separate orders based on your institution. This is important information for anesthesia purposes if you are planning a surgical resection. It is important to note that these masses should not be biopsied for tissue diagnosis if you suspect paraganglioma. They are extremely vascular and present a high risk for hemorrhage.

Imaging

Most paragangliomas of the head and neck are initially characterized on CT scan during the workup of a new neck mass. Paragangliomas will typically avidly enhance with contrast and have a delayed washout due to their rich capillary network. When the paraganglioma approaches the skull base, you may also see erosion of adjacent bone and involvement/compression of skull base foramina.

On MRI, paragangliomas will be T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense, with a classic "salt and pepper" appearance on T1 imaging. This is due to the flow voids in the vascular network, with the "salt" describing the bulk of the mass and the "pepper" being the dark spots of the flow voids.[1]

Angiography will demonstrate a classic "Lyre sign", in which the internal and external carotid arteries are splayed apart from the mass effect between them.

-

Carotid body tumor angiography with the internal and external carotid artery separated by mass effect.

-

A Lyre, for reference.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with paragangliomas, particularly in the jugulotympanic distribution, can present with the various eponymous jugular foramen syndromes:

| Syndrome | CN IX | CN X | CN XI | CN XII | Sympathetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vernet Syndrome | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Collet-Sicard Syndrome | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Villaret Syndrome | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Tapia Syndrome | ✔ | ± | ✔ | ± | |

| Jackson Syndrome | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Schmidt Syndrome | ✔ | ✔ |

In addition, the following diagnoses should be considered:

- Schwannoma

- Arterio-Venous Malformation

- Metastatic Malignancy

Management

Medical Management

Surgical Management

Outcomes

Complications

Prognosis

References

- ↑ Gaillard F, Campos A, Hartung M, et al. Paraganglioma. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 11 Sep 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-1843